The relationship between space and function has been one of the key defining questions in modernism. However, as Bill Hillier explains, ‘[o]ne scours the architectural manifestos of the twentieth century in vain for a thorough going statement of a determinism from spatial form to function, or its inverse’. Yet, there is a relationship of some sort between what goes on in buildings and their form. For Hillier, ‘[s]pace is more than a neutral framework for social and cultural forms. It is built into those very forms. Human behaviour does not simply happen in space. It has its own spatial forms.’ If function is a vague term, having, as Adrian Forty explains, at least five different definitions (and this prior to 1930s), what about space and social behaviour? Can architects design space so as to create affordances for social behaviour? And what happens after the design is finished, or rather how do people actually behave in space?

Focusing on these questions, Chenyang Li, a student in my Architectural Phenomena module at the SSAC MSc course at UCL embarked on testing the limitations of the influence of space on social behaviour. His starting point was a study I had carried out in the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA) in 2005 (supported by seed funding from the University of Michigan), which coincided with the opening of the museum extension designed by Yoshio Taniguchi. The results of the study were published in my book Architecture and Narrative by Routledge (2009). In this study I explored the relationship between architectural design and exhibition design in the 4th and 5th floor galleries, alongside the impact they had on the exploration patterns of visitors. The research revealed that comprehensive museums like the MoMA construct spatial and visual histories of art through the placement of art works, and the spatial design of exhibitions. They thus, influence the relationship between the designer, the curator and the visitors in ways which are laden with political messages and institutional visions. A similar investigation by Kali Tzortzi in The Journal of Space Syntax, also emphasized the importance of spatial design, describing learning in museums as ‘meaningful experience’ rather than ‘defined content outcome’. Starting from these studies, Chenyang asked whether space can have a role in shaping people’s behaviour in buildings that serve different functions.

If museum design, Chenyang asked, manipulates spatial relationships to construct a certain interface between people, space and objects, can the same be said about buildings where society has a stronger hold on rules of behaviour?

Chenyang looked next at a study I did with Cauê Capillé on two libraries in London. Analysing the spatial layout of Swiss Cottage Library and the Kensington Central Library in combination with empirical observations of human activity inside the buildings , Cauê and I found that in the Swiss Cottage Library, the interface between space, programme and social behaviour was weekly structured, creating an informal environment with ample opportunities for both interaction and focused work. In the Kensington Library on the other hand, social rules for noise control dictated a strongly structured interface between space and behaviour. Using these two libraries as examples, we argued that architects can weaken the influence of strong programmes on the actual use of buildings. Design has a role to play even in buildings that invest strong control over space and programme such as libraries, creating a spatial culture that alleviates and even transforms the rules of social behaviour. Research by Bill Hillier, Julienne Hanson and their colleagues at UCL has shown that densities of occupation, interaction, movement and use are higher in highly integrated spaces, that is, spaces that are topologically closer to every other space in layouts. Segregated spaces on the other hand that are difficult to reach tend to have lower occupation values. By looking at space in this way, we can begin to see both how social and cultural patterns are imprinted in spatial layouts (the Kensington Library), and how spatial layouts affect the functioning of buildings (The Swiss Cottage Library).

To further understand our proposal, Chenyang carried out observations in the Swiss Cottage Library additional to our original study. According to his immersed field work, the SCL’s space and programme encourages people to move through the entire building, covering many of its areas. Different types of visitors and their paths were mixed on the first floor, which also has the highest level of interactions. However, fewer interactions were taking place early in the afternoon (3 p.m.) compared with the evening hours (6 p.m.). In an interview with the manager of the SCL, it was revealed that this library is used by a large number of students after 4.30 p.m. for study and group work. There are five schools within a twenty-minute walk from this library, including the UCL Academy, which is only 200 meters away. Therefore, there are different types of users, each with their different use patterns based on different times of the day. Before school time, the SCL is mainly visited by individuals to borrow, work and read. Later in the day, study groups from the neighbouring schools visit the library to finish their assignments through discussions. The proportion of social interactions in the building sees a considerable drop after removing this particular group of people. So the increase of interactions in the evenings is caused by these study groups which visit the library with a specific purpose, rather than the natural power of space to facilitate unprogrammed encounters other than those originally intended.

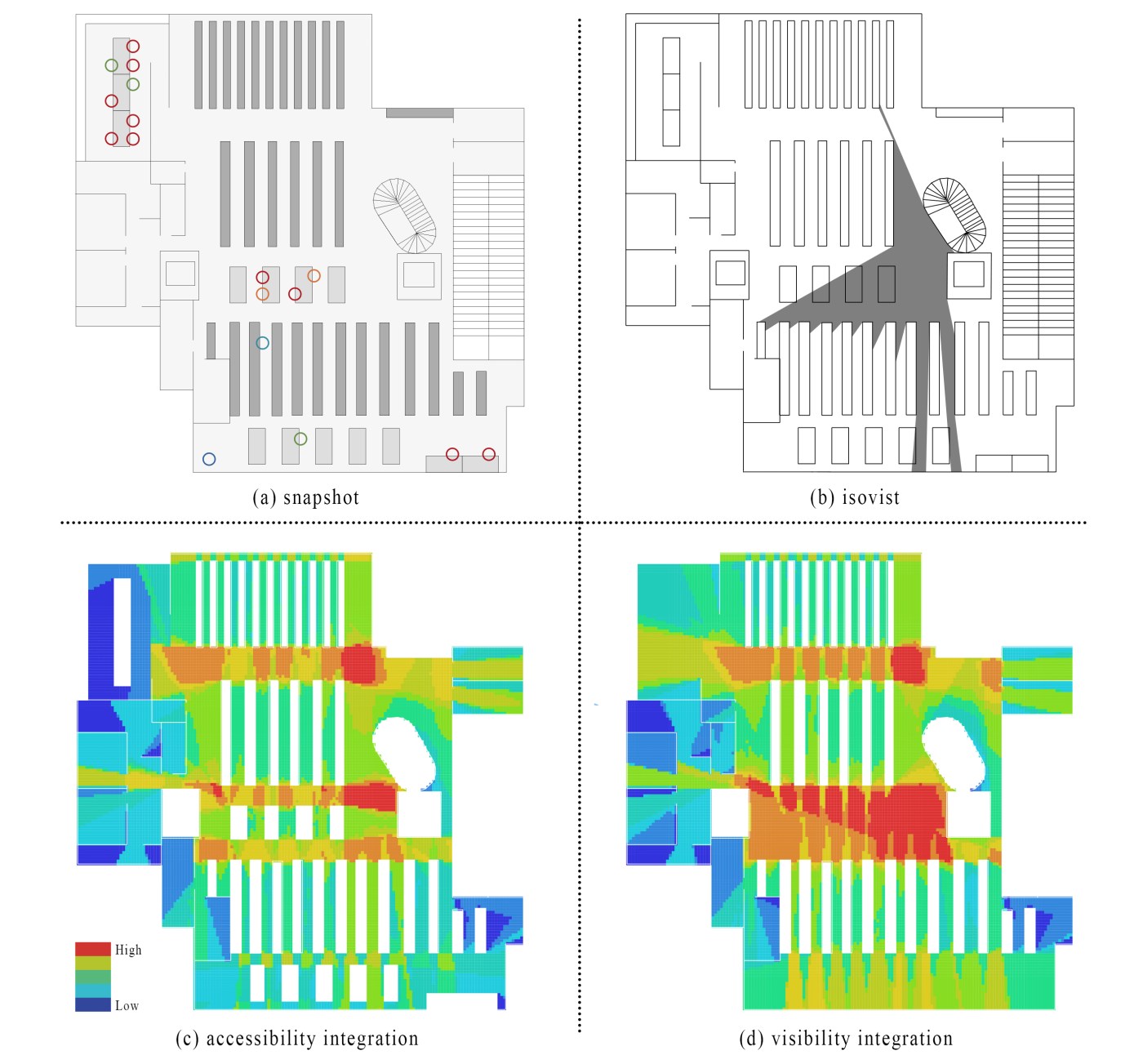

In order to understand how people use libraries more generally, Chenyang did a second study, this time in the Library of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL. Located on the lower ground floor of the School, this library is not open to general users. Only UCL students and staff can enter it using their identity cards. Based on previous research by Hillier and his colleagues, it is reasonable to expect, that the central area of this library, with high levels of integration in relation to accessibility and visibility would be highly used by students. Chenyang’s immersed observations showed that the opposite was the case. Most people who were studying and reading at the time chose areas with low levels of visual integration located in the northwest corner of the layout (shown in blue colours). In contrast, only four students were using the central learning area, two of which were relaxing rather than studying. These results help question the simplistic extension of research findings from museums and office spaces to all kinds of building types and users.

In our study of the SCL, Cauê and I had explained that libraries are supposed to ‘shift pedagogical and learning approaches from the didactic model of learning to collaborative interactive forms of learning, supporting learner-led activities and innovative forms of thinking.’ The Swiss Cottage Library achieves its goal for student groups, despite their distinctive characteristic. Nevertheless, for other individual citizens, space may instead have a negative impact on their use.

Chenyang concluded that space has the potential of overcoming the strong rules of organisational programmes about behaviour in buildings, facilitating unpredictable encounters and communication between people. All other factors being equal, such as context, culture etc., architects can use spatial design to weaken strong social programmes, designing for the indeterminate and the unprogrammed. It is worth stressing that this has been the purpose of many architectural approaches in the 60s, which starting as a reaction against authority and uniformity ended in the service of organisational purposes and the knowledge economy. With such lessons learned, architects should be aware of the complexity of organisational goals, and the potential conflits between these goals and the real needs of users in order to meet these goals. Equally important to this, is for critics of architecture and researchers to develop more salient concepts (other than function) and approaches – capable of handling complexity, diversity, power and conflict in terms of social behavious – in order to understand the relationship between buildings and the life that takes place inside them and around them.

References

Capillé, C.; Psarra, S. (2014) ‘Space and planned informality: Strong and weak programme categorisation in public learning environments’. A|Z ITU Journal of Architecture.

Forty, A. (2000) Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture, London: Thames and Hudson.

Hillier, B. (1996) Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Psarra, S. (2007) Architecture and Narrative: The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning. Routledge; 1 edition.

Tzortzi, K. (2010) ‘Space: interconnecting museology and architecture’. The Journal of Space Syntax, Vol 2, No 1 (2011).

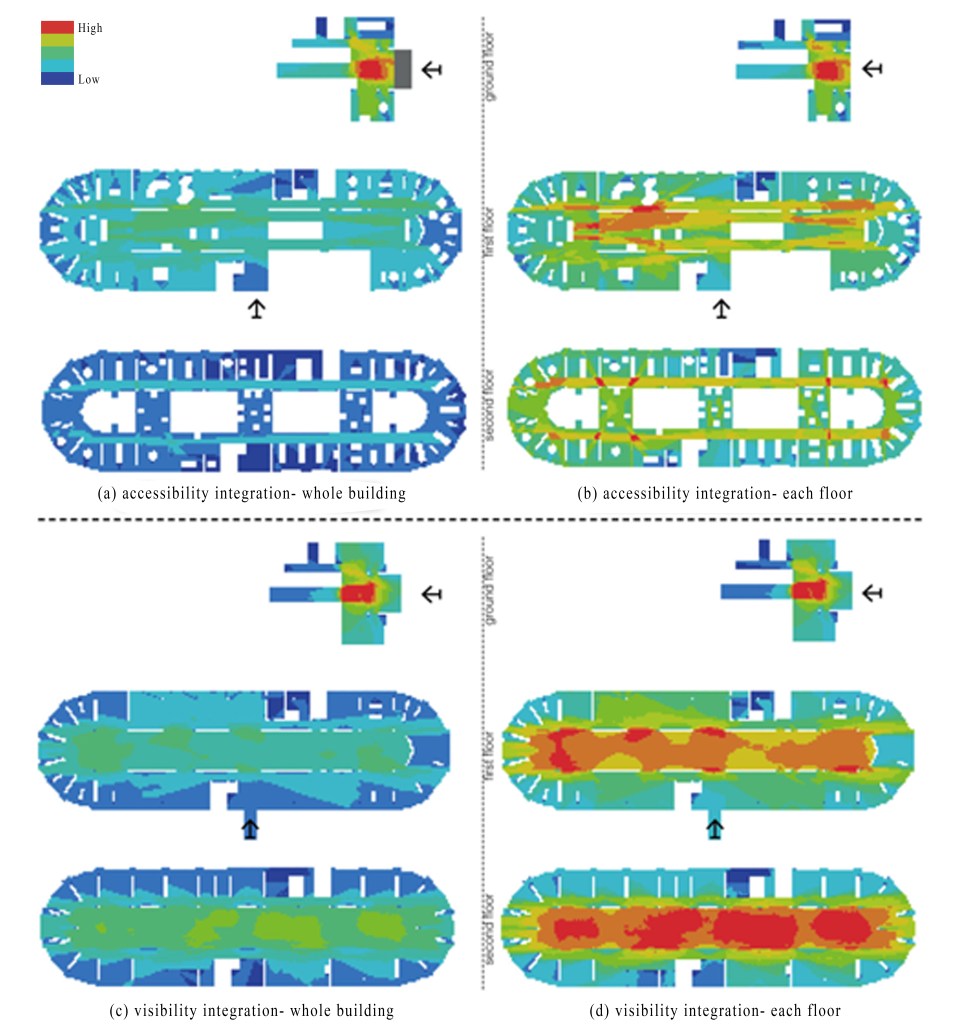

To further understand our proposal, Chenyang carried out observations in the Swiss Cottage Library additional to our original study. According to his immersed field work, the SCL’s space and programme encourages people to move through the entire building, covering many of its areas (Fig.1a). Different types of visitors and their paths were mixed on the first floor, which also has the highest level of interactions. However, fewer interactions were taking place early in the afternoon (3 p.m.) compared with the evening hours (6 p.m.). (Fig.1b&Fig.1c). In an interview with the manager of the SCL, it was revealed that this library is used by a large number of students after 4.30 p.m. for study and group work. There are five schools around this library within a twenty-minute walk, including the UCL Academy, which is only 200 meters away. Therefore, there are different types of users, each with their different use patterns based on different times in the day. Before school time, the SCL is mainly visited by individuals to borrow, work and read. Later in the day, study groups from the neighbouring schools visit the library to finish their assignments through discussions. The proportion of social interactions in the building sees a considerable drop after removing this particular group of people (Fig.1d). So the increase of interactions in the evenings is caused by these study groups which visit the library with a specific purpose, rather than the natural power of space to facilitate unprogrammed encounters other than those originally intended.