Can you fit a supermajority into a space designed for confrontational politics on opposing benches and maintain the political culture?

According to the former Labour leader, Neil Kinnock, the extraordinary thing about the Commons Chamber is that when it is operates as an entralling theatre ‘it can ultimately bring down the government, because of authentic fluent, deadly passion on a major issue’, writes Ian Dunt in his 2023 book How Westminster Works and Why it Doesn’t. Many politicians have referred to the seating layout of the Commons debating chamber and the contribution it makes to the temperature of the debate. Foremost among them was former Prime Minister, Winston Churchill who insisted on re-building the Commons chamber after war damage in 1941 exactly as it was with government and opposition facing each other across a despatch box. Its shape should be oblong he declared, ‘and it should not be big enough to contain all its members without overcrowding’. He wanted to see the whites of the eyes of the opposition and ensure the density in the chamber and the intensity of debate were maintained.

There is a widespread argument that opposing benches foster opposition while semi-circular layouts promote co-operation. To find out, we interviewed a number of parliamentarians from the Commons and the Lords. Where members are located in the Commons chamber already sets the tone of the debate, and these very public political relationships, my own MP, Tulip Siddiq, explained. She commented that if the government and the opposition benches are two swords -apart, ‘they want us sword-fighting’.

But this may oversimplify the matter. There is more to the spatial layout than the notorious distance of two-swords and the symbolic expression of the two-party system by the opposite benches. In our conversations, Lord David Anderson pointed out that the dynamics of vision when seated in the chamber can offer an insight into relations of power and control. Although the chamber layout may speak to the two-party political system, it provides a simple, sometimes misleading picture.

In addition, modes of executive – legislative relations concern not simply the government-opposition but also other groupings between party groups. In response to an observation about the enemy on the opposing benches, Churchill responded by declaring the occupants of the opposing benches as ‘Her Majesty’s Opposition’. He went on to observe that the enemy was behind him, capturing both the visible and hidden spatial dynamics of conflict and competition in politics.

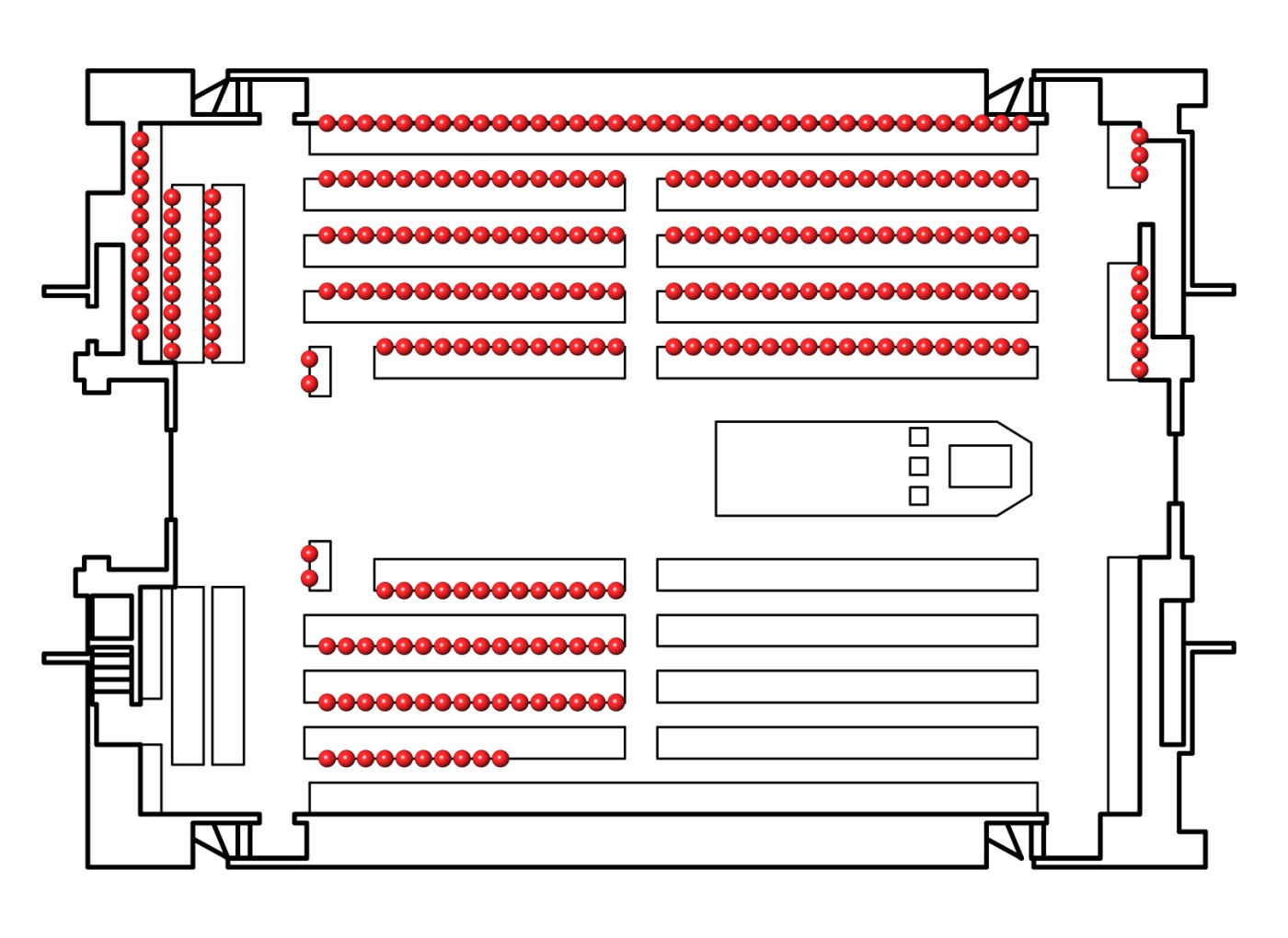

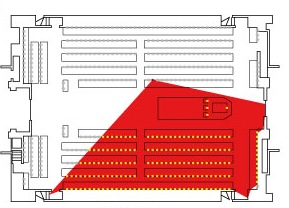

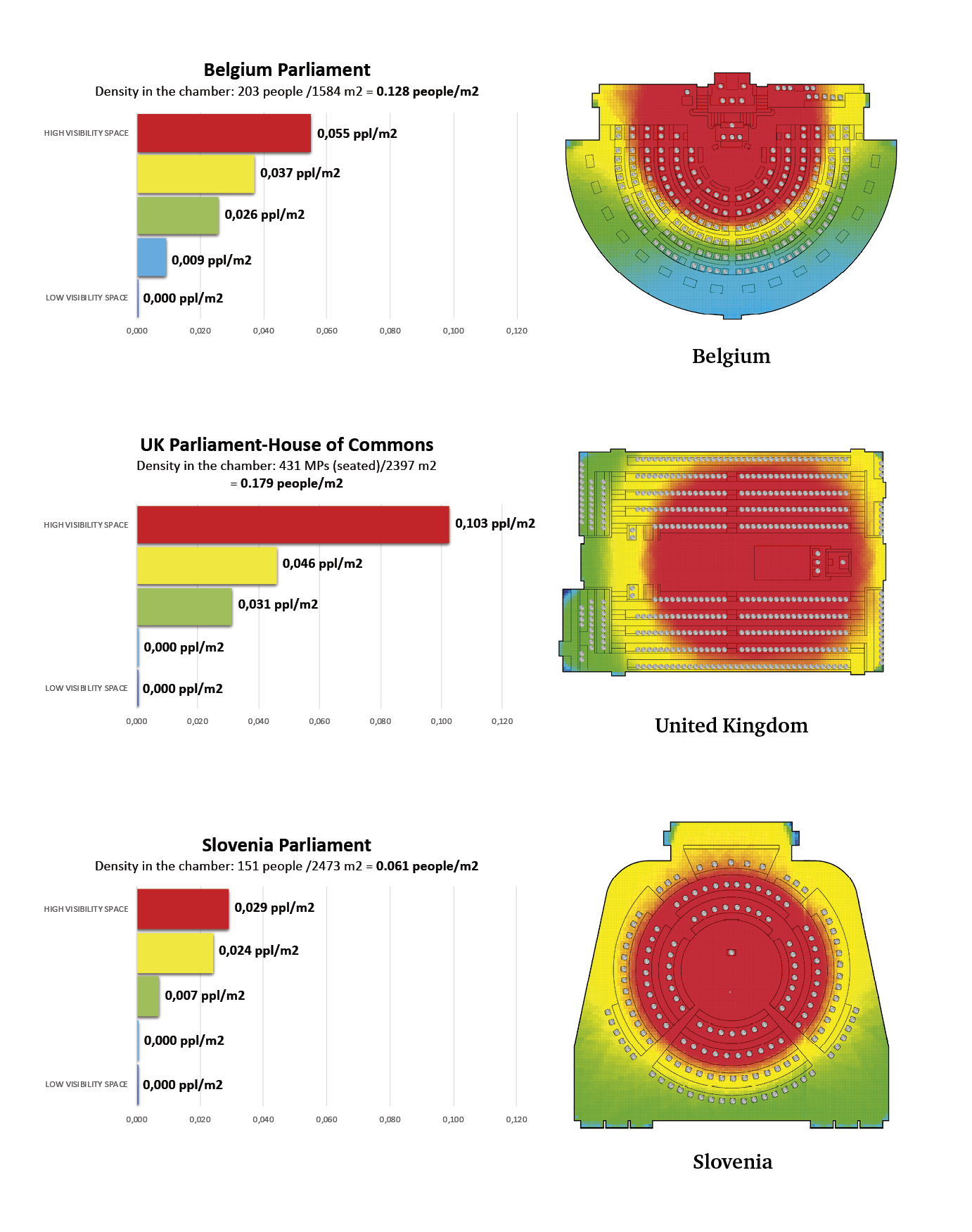

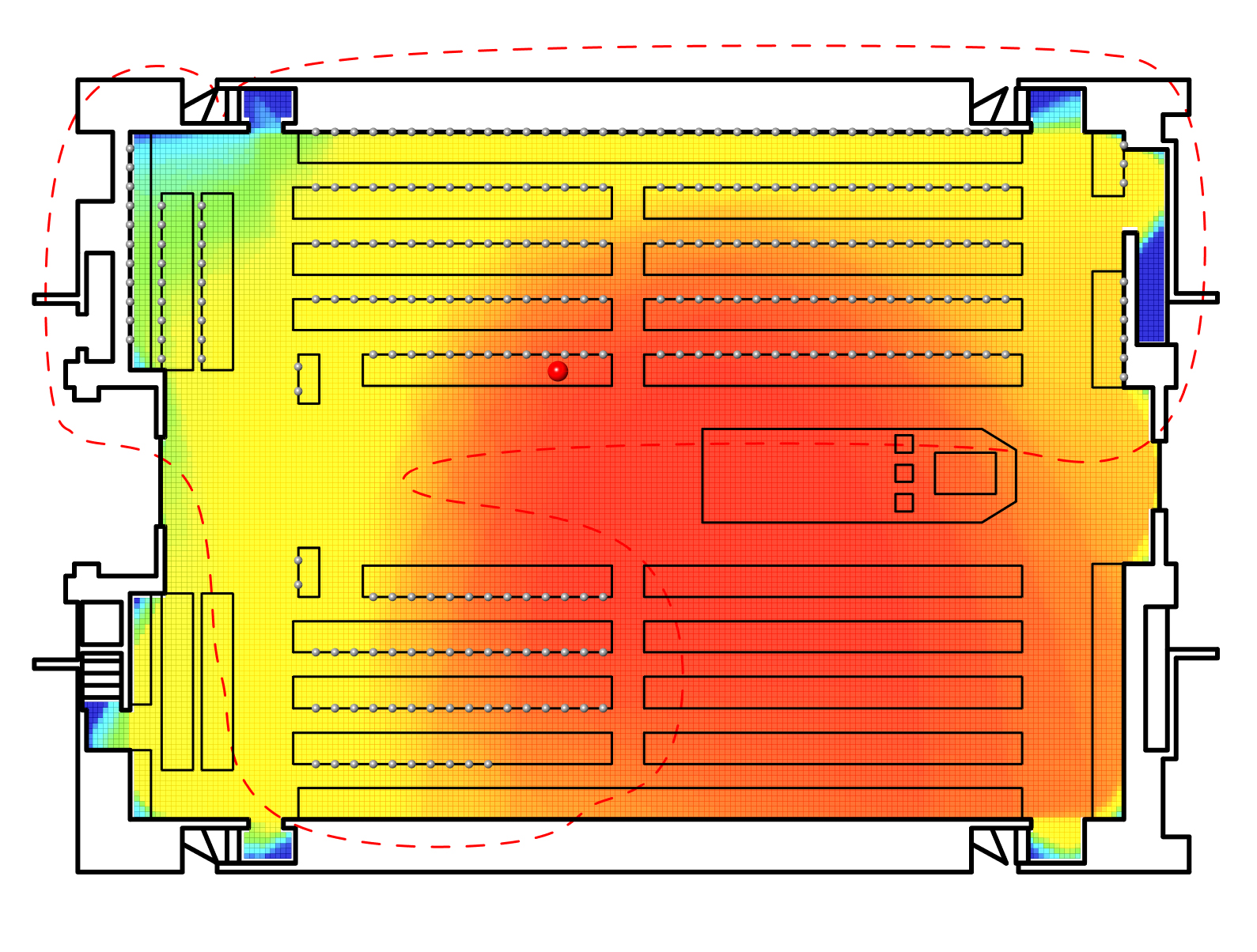

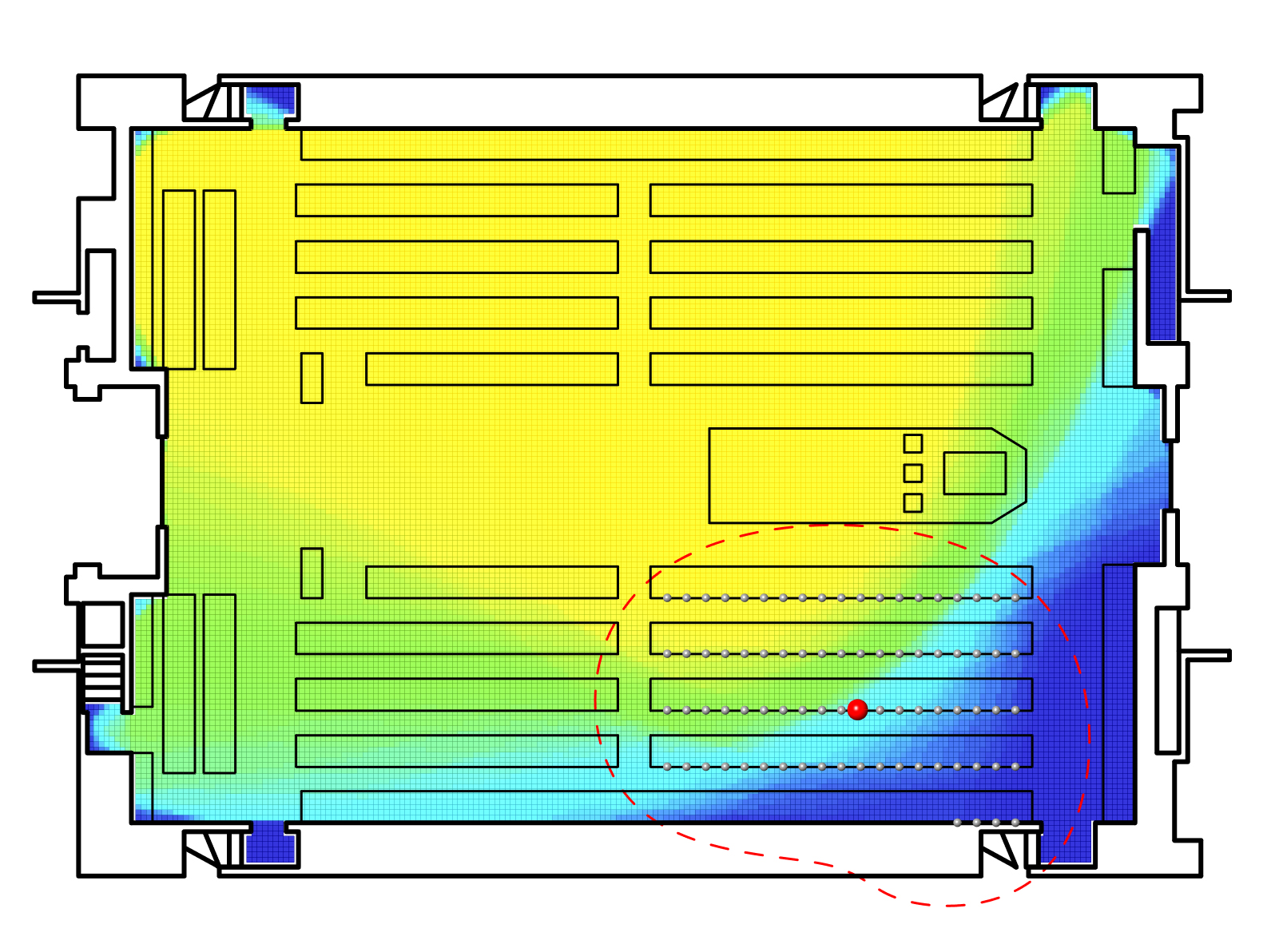

Where members sit in the debating chamber signifies their status, with a seat on the front benches on the government side indicating a member of the cabinet and the back-bencher rows behind making up the rest of the parliamentary party. The official opposition follows a similar arrangement in ‘shadow’ form. As to the visibility dynamics, in a study we conducted with Naomi Gibson and Gustavo Maldonado in the 2023 anthology Parliament Buildings: The architecture of politics in Europe we looked at how different layouts of debating chambers can give visual prominence to parties sitting in one part of the chamber or another. We mapped the area viewed from the vantage point of each individual seat, and by overlapping all views we found the most observed areas (sq. m. expressed according to visibility strength from red to blue), and the distribution of density in each of the visibility zones in the Commons and four other plenary chambers in Europe.

The view of the Prime Minister (left). Visual connectivity within the plenary halls alongside density of high and low connectivity areas (right) © Gustavo Maldonado

Our study showed that:

- Placing the unequal categories of government and opposition face-to-face in a closely spaced chamber of equal levels of visibility for all parties can in fact subtly redress the imbalances in power.

- Among those chambers we examined, the House of Commons has the highest absolute density, and the highest density within its high-visibility zone (shown in red). When it exceeds capacity as there are not enough seats for all MPs the density is pushed even higher. The shape and seating arrangement of the Commons mean that there are very few MPs that are not co-visible with other MPs in the chamber.

- Backbenchers command an all-encompassing view of the House compensating for their lower status.

Why are these characteristics important? They are important because it is necessary to attract the Speaker’s attention in order to speak in the debate. Other parliaments have seating arrangements where some of the seats are less prominent but this is addressed by MPs indicating electronically that they wish to speak. This even distribution of visibility is one of the strengths of the House of Commons and gives a theatrical and physical dynamic to proceedings as MPs also need to rise to their feet to indicate their desire to speak or to interrupt a speaker.

How will this dynamic be affected by the 4th of July 2024 election?

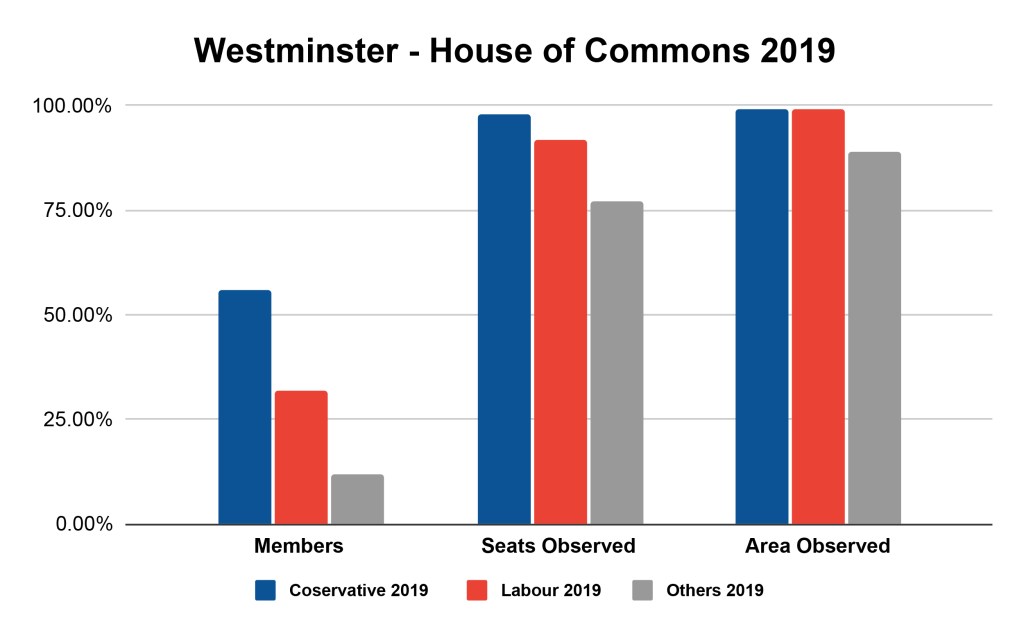

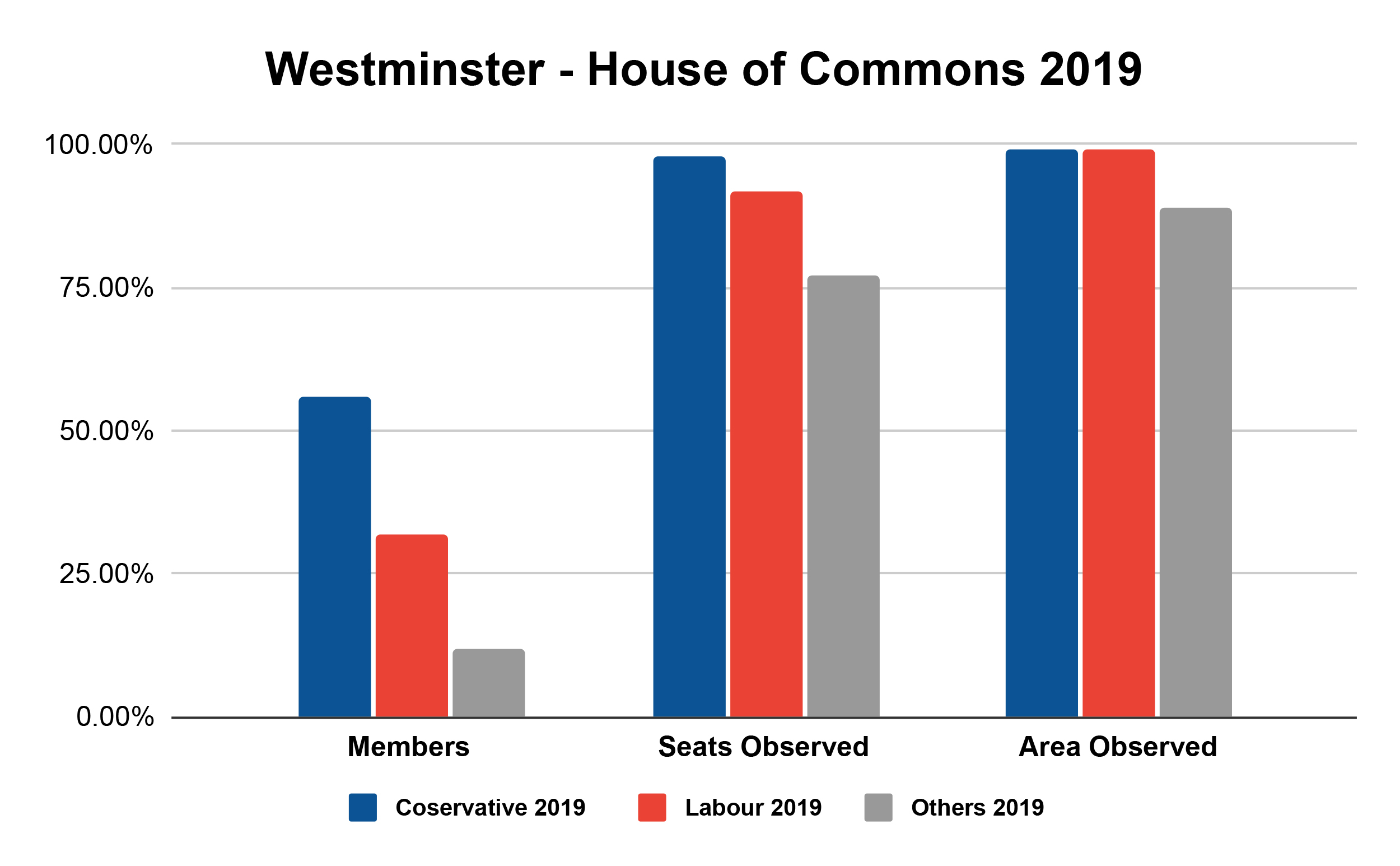

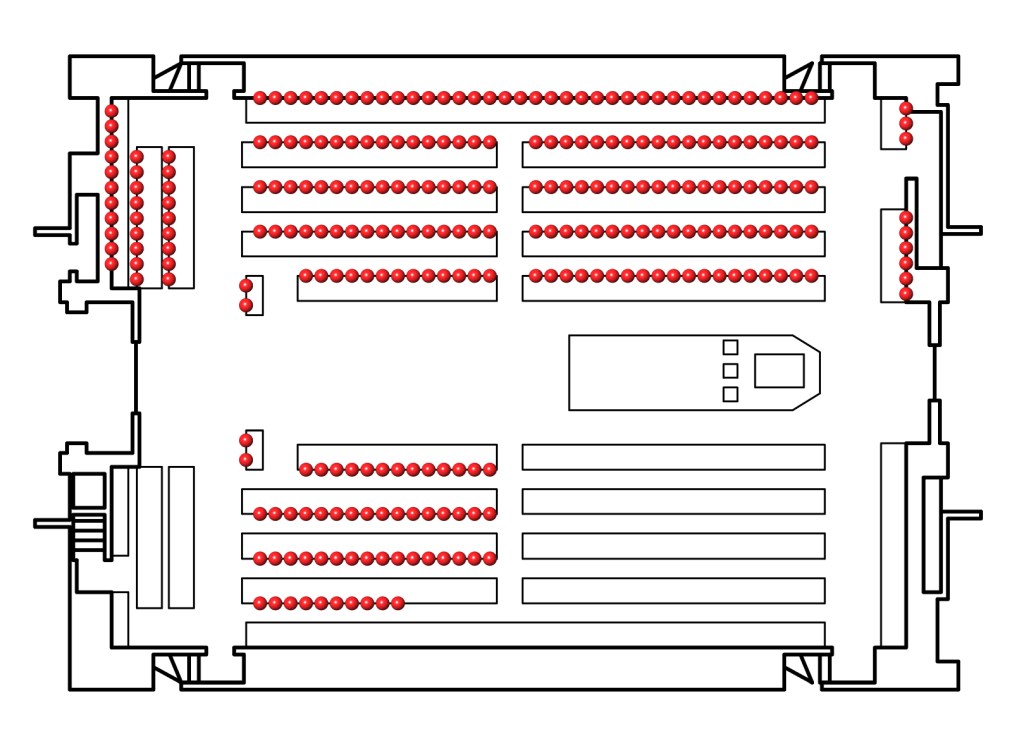

Following their landslide victory last week, Labour now commands a dominant 63.4% (from 32% in 2019) of seats in parliament. The Conservatives have dwindled from 56% to 18.6%, and other parties have risen from 12% to 17.9%. What will be the embodied dynamics of power when the House is full? How will this power be distributed in the existing layout given the deliberate intention to have government MPs sitting on one set of benches and the rest sitting on opposition benches, leaving no doubt about whose side MPs are on? As there are only 427 seats in the chamber, will the government party now occupy the opposition benches?

Gustavo Maldonado and I repeated the study of visibility dynamics to reflect the composition of the new membership of the 2014 Commons .

- Labour: In 2024, Labour’s dominant representation translates to 97.67% of seats observed and 99.50% of the area observed, an increase from their 2019 figures of 92.00% and 99.00%, respectively. This growth in embodied visual control suggests that Labour MPs now have almost complete visibility within the chamber, extending their visual dominance in parliamentary proceedings.

- Conservatives: Conversely, the Conservative Party’s reduced representation in 2024 (18.6%) corresponds to a significant decrease in both seats observed (87.93%) and area observed (96.50%), down from 98.00% and 99.00% in 2019. This reduction indicates a contraction of their visibility and spatial influence.

- Other parties and independents: The visibility for other parties has improved with 87.50% of seats and 96.00% of the area observed in 2024, compared to 77.00% and 89.00% in 2019. This increase reflects a growing visual influence of smaller parties within the chamber, indicating a more pluralistic parliamentary environment.

Yet, in spite of the marked differences of political representation shown in the figure below and although the number of seats and the area observed has reversed for the Labour and the Conservatives, these are still broadly similar for all parties. The equally distributed views in the chamber, will continue to give an almost equal spatial footing to the very unequal distribution of power.

July 2024 – Visibility of the governing party (produced by overlapping views from every Labour seat) (top left). Visibility of Conservative party (top right) and other parties (middle right). Numbers of Members seats observed and area observed in 2019 and 2024 elections (bottom left and right respectively).

It is important of course to consider what one sees when trying to speak in the chamber. Someone speaking from the opposition will be facing rows of opponents, stretching from left to right (and also to their sides?), ‘creating a wall of human disdain’ as Ian Dunt puts it in How Westminster Works. Their inner strength to press with their attacks should rise in reverse proportion to their reduced decibels of encouragement or abuse.

The enthralling theatre of the Commons Chamber and its new composition of embodied politics holds thus a series of questions: Would the new composition mean a change in the political debating culture? What happens when the governing party backbenchers seat opposite facing the governing party, or when the swordsmen are actually sitting beside each other opposite the government? Will the opposition feel more threatened or will the government party MPs on these benches become more moderated? Do they need a new nomenclature to signify their government status, yet sitting on opposing benches?

Will, in this new seating dynamics, the government backbenchers take advantage of their seating opposite the government to rebel? Will seating arrangements facilitate dissident government back-benchers to join forces with the opposition backbenchers for influence and support? As Anthony King explains, the government needs backbenchers for moral support and for their votes. The backbenchers need the government for resources….The aim with regard to the other party is to defeat it; the aim with regard to one’s ow party is to bring it round to one’s. point of view.’ One discounts the disapproval of the other party; the disapproval of one’s own is harder to bear.1

There is another point. This arrangement whereby the governing party MPs are sitting on the opposition benches might be seen as approaching the proximal arrangements of the semi-circular chamber well known for their large number of parties of which various combinations come together to form coalition governments. Since we may now observe that the UK’s former monolithic two-party system may actually conceal an underlying coalition where the views of different groups are voluntarily suppressed to maintain the dominance of the larger organisation. What if some of these groups becomeing increasingly disaffected with the larger party, begin to peel away from it and choose to sit as quasi opposition on the opposition benches giving spatial expression to their differences?

- Anthony King. “Modes of Executive-Legislative Relations: Great Britain, France, and West Germany”, Legislative Studies Quarterly , Feb., 1976, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Feb., 1976), pp. 11-36 ↩︎